[ I know R. Nandakumar through his writings on photography and art. In the year 2005, I met him in Trivandrum during artist K. Prabhakaran’s exhibition. A common friend, Lt. K. Ravindran (Chinda) connected us. Those times, Joesph Chakola was opening his new gallery called ISHKA. The inaugural show was a solo show of mine titled ‘Animals’ curated by R. Nandakumar. Below is the curatorial note. R. Nandakumar now lives and works in Delhi. He has received Nehru Foundation Fellowship 2014.

– Abul Kalam Azad ]

R. Nandakumar, on the photography of Abul Kalam Azad

If representations positioned subjects ideologically then a politics of photography had a broadly political role to play in contributing to the transformation of dominant forms of subjectivity. It was less a case of theorizing photography than placing photography in a theoretical relationship to politics.

– John Roberts

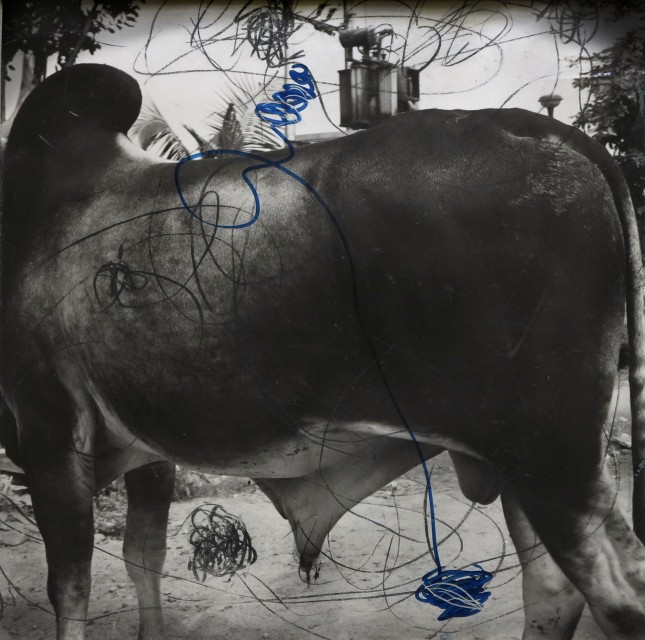

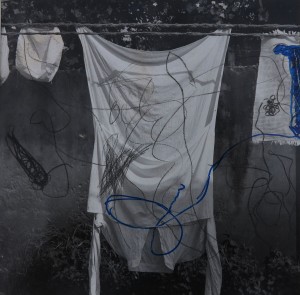

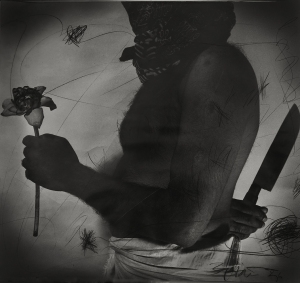

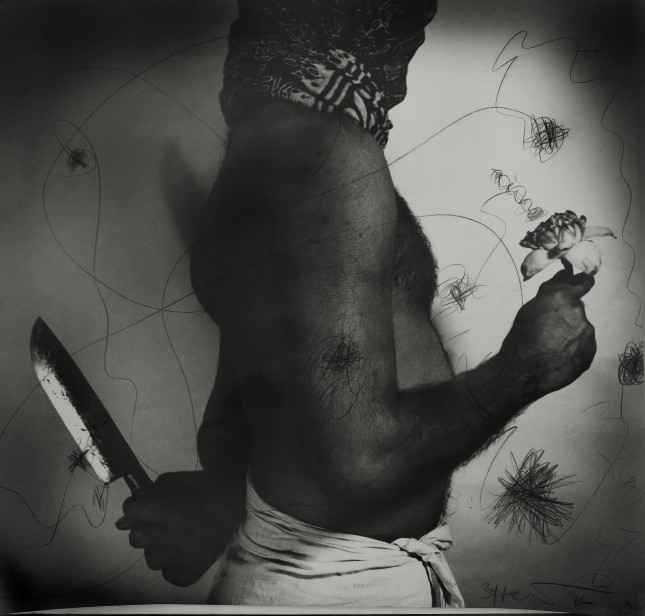

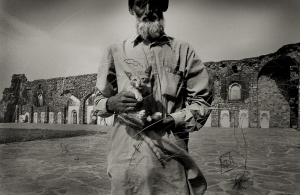

Man with tools / Photograph (C) Abul Kalam Azad / Single edition/ Painted photographs on canvas / 2012

Ever since the modernist phase, photography has moved into the aestheticised institutional space of the gallery, subjecting itself to the protocols of the gallery system and finding its place in the arts discourse, rather leaving behind the context of the portfolio editions and the mass circulation illustrated magazines, through the curatorial efforts of the likes of Edward Steichen, Alfred Stieglitz and John Szarkowsky. But for photography to be faced with the threat of aesthetic closure in which the modernist norm of self-referentiality amounted to a refusal to communicate, was plainly a contradiction in terms. While the snapshot tradition of the family album and the ephemera of the free-floating vernacular photography in its ubiquitousness have been appropriated into the canon of modernism, it got an aesthetic legitimacy in the name of pop. However, the process of aesthetic appropriation had invariably blunted the political edge and played down the social relevance of the factographic and the reportorial functions of the early documentary tradition and its contribution to a realism of the everyday as by the workers’ photography movement. As most of the theorists of modernism had conferred the long-awaited artistic status to the photographic image, it had at the same time liberated the medium from some of the long-debated conceptual and theoretical issues centred on the problematique of the ‘ontology of the photographic image’ (to say after George Santayana), especially in its indexical relation to reality. However, this shift by no means took photography to the untroubled area of the aestheticised image production by attracting and invoking the normative preconditions for it in terms of the signature style, the authorial presence and the ‘singularly’ artistic disposition of the photographer. On the contrary, its new uses in the ‘art’ tradition has again aligned it to a more radical practice with political orientation as in the works ranging from photo-conceptualists like Victor Burgin to Jeff Wall, Jo Spence and Cindy Sherman. The contradictions here are too glaring to be overlooked by any sensitive practitioner as, for one thing, such a practice has to take recourse to the ways of the art world even as it finds itself at odds with it. Like any radical artists anywhere who have learned to live with these contradictions even as they feel called upon to resist them by problematising the very relations that define their subject position vis-à-vis the Art (with A capital A) Establishment and get the better of them, Abul Kalam Azad in choosing to do what he does as a photographer, does not assign his works to be subsumed under the aestheticised notion of ‘official’ art photography predicated on signature styles.

Man with tools / Photograph (C) Abul Kalam Azad / Single edition/ Painted photographs on canvas / 2012

Preoccupied with the contradictions and aporias involved in the critical practice of the photographic medium, Azad can be seen to be addressing some of the tenuous issues that have been haunting the medium and the social and political implications of its theoretical premises in the postmodern Indian context. For one thing, Azad has an ambivalent relation to the legacy of the positivist-realist aesthetic underpinnings of the produced image in its representational function as upheld in the reportorial-documentary tradition, though the latter has for long been his remit in his career of photojournalism. At the same time as he creates an ambivalent zone of referentiality around the image as signifier, Azad does not go all the way to negate the referential function of the photograph as the realistic image of reality by divesting it of its indexicality. In a sense he has been consistently trying to circumvent the instrumental rationality that has been invariably associated with the medium by reworking the transparency of the ‘obvious’ as a kind of counter thrust against the empirical facticity of ‘correspondence’. The various non-perspectival (and anti-graphic) stylistic means that Azad employs as a visual strategy to under-narrativise the ‘obvious’ in his work have in fact a bearing on this concern. As for example, to create a pictorial space that is different from the monocular in its function as the field of spatial signification, he evokes an afocal and non-projective space as the site of (pictorial) articulation. It is in this context that the differential focus that he uses in the Divine Façade series or the soft focus he uses in the Black Mother series has to be seen. Though his preferred medium remains basically the analogue, he has of late turned to digital mode because of the possibility it offers in countering the claims to unmediated ‘truth’ of the specular image as representation that characterise the chemically produced image. Related to this is also why, even from earlier on, he has been scratching the negative with doodles in an attempt to deface and mar the glossy cosmetic finish of the print surface which in corporate photography has been used to equate the ‘quality’ (technical) of produced image with a specific ‘value’ (aesthetic).

Over all, the corpus of Azad’s work can be seen to have a thrust towards an archive of local micro-history at the level of personal memory and in that sense, his works add up to a kind of social anthropology of his land and its people, though not necessarily in the line of tradition of the objective documentary. In fact, the antiquated mediaeval-looking small town environment of Mattanchery in central Kerala (where Azad presently lives) with its still visible colonial legacy bequeathed by the successive foreign rulers from the Portuguese and Dutch to the British, forms a world by itself in his photographic oeuvre, with its local legends and local worthies. Coming under the influence of the savant and social reformer of the early part of the last century in Kerala, Sree Narayana Guru, Azad’s work is informed by a worldview that is evidently a convergence of the two strands of progressive social thinking and a form of spirituality that does not deny the material world. This can be seen from the way Azad thematises his perceptions of the unheroic and mundane local history through the tableau of his staged ‘realism’ as much as in his use of the predominantly sombre tonality of the monochrome in most of his work. Added to this is the choice of his angle so as to enframe spatial vista that is allusive of the sky s the realm of aether and an aspect of the elements in cosmological reckoning. Here the richly nuanced monochromatic tonality, though it adds a certain crepuscular lyricism to most of his work, is more than anything expressive of a certain ambivalence in his attitude to the phenomenal world of appearances as is only consistent with his perceptions as mentioned before.

UNTOUCHABLES / Photography (C) Abul Kalam Azad / Archival pigment prints / 2000 – 2005

UNTOUCHABLES / Photography (C) Abul Kalam Azad / Archival pigment prints / 2000 – 2005

UNTOUCHABLES / Photography (C) Abul Kalam Azad / Archival pigment prints / 2000 – 2005

UNTOUCHABLES / Photography (C) Abul Kalam Azad / Archival pigment prints / 2000 – 2005

UNTOUCHABLES / Photography (C) Abul Kalam Azad / Archival pigment prints / 2000 – 2005

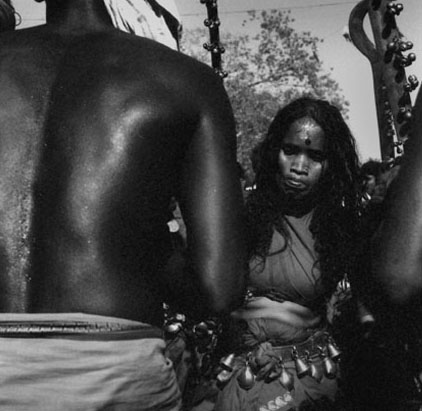

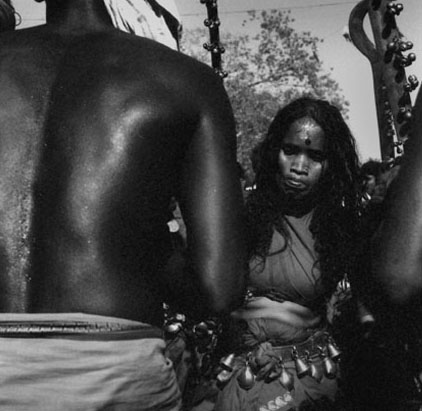

Black Mother series, done during the period from 2000 to 2003, on his return to Kerala after a stay outside, depicts the female oracles at the time of the festival at the Devi temple at Kodungalloor which is related according to local legends to the myth of Kannaki. These oracles in the various stages of trance, can be seen stomping around, sword in hand, in convulsive movements of frenzy. Weird-looking in their hysteric outbursts, the women oracles are part of the temple functionaries who devote themselves at the service of these unique customs and rituals observed in the temple that are related to ancient and possibly, pre-Brahminic mother goddess cults. Though the atmosphere is charged and overwrought with a kind of high-strung atavistic fervour, the images of these women in their redemptive bodily movements of self-mortification, have hardly any religious awe about them. Far from the casual gaze of an outsider looking at an esoteric spectacle in bemused curiosity, Azad’s register of visual engagement in these works, at the same time, eschews that of subjective identification at the level of a participant or devotee though the choice of his angle is perfectly in empathy with what is seen at that level of experience. Whether the figure of the oracle or some ritual object on the ground, his angle keeps them on level with the camera eye which does not necessarily correspond with that of the normally positioned human eye. He allows a certain intermediary spatial distance so as not to foreground the figures by letting them loom large within the frame. Though there is a conscious avoidance of any high-definition clarity of the image, the remnants of the ritual paraphernalia in the background and the ritual trappings on the body of the performer are an invariable part of the composition such that they together inflect meaning tangentially in a different direction. This becomes clear when the oracle series (significantly called “Body, Blood and Song” originally) is read alongside the other series called “Goddess” – both challenging the accepted notions of the cultural stereotypes of feminine subjectivity in relation to the female body. Though the frame itself emphasises frontality of point of view, the figures in the former are at times partially left out or cut at half length or are silhouetted but, however, are invariably seen with their ritual accoutrements like the anklet, the sword, the string of bells around their waist, etc. These part objects (as partial drives, in the Lacanian sense) evoke a specific referential field in the whole range of Azad’s work as the metonymic image. For instance, the anklet, here though in the context of the specific ritual has feminine connotations through its mythical associations with Kannaki, the protagonist of the myth, is in the performative context gender-free as it is worn by both male and female oracles as well as performers of other dance forms. However, the sword that the female oracle wields and with which she inflicts self-torture, has culture-specific and trans-cultural phallic associations, to follow the argument of David Shulman in his study of the local Tamil versions of the Mahishasura Mardini myth. Considering the fact that the occasion is also marked by the loud and uninhibited singing of frankly erotic songs replete with pornographic details, especially by women, the psycho-somatics of trance as the interface between devotion and deviance, mark a form of gender transcendence and switching of identities through the bodily experience of the ritual. The withered and world-weary look on these abject faces that is unrelieved by even the ritual trappings that attest to their sanctified status, makes of them less of any divinity than what is discreetly suggested of their socially marginalized existence.

‘Black Mother’ – Heroine of Silapathikaram / Photography (C) Abul Kalam Azad / Bromoil prints / 2000

‘Black Mother’ – Heroine of Silapathikaram / Photography (C) Abul Kalam Azad / Bromoil prints / 2000

‘Black Mother’ – Heroine of Silapathikaram / Photography (C) Abul Kalam Azad / Bromoil prints / 2000

‘Black Mother’ – Heroine of Silapathikaram / Photography (C) Abul Kalam Azad / Bromoil prints / 2000

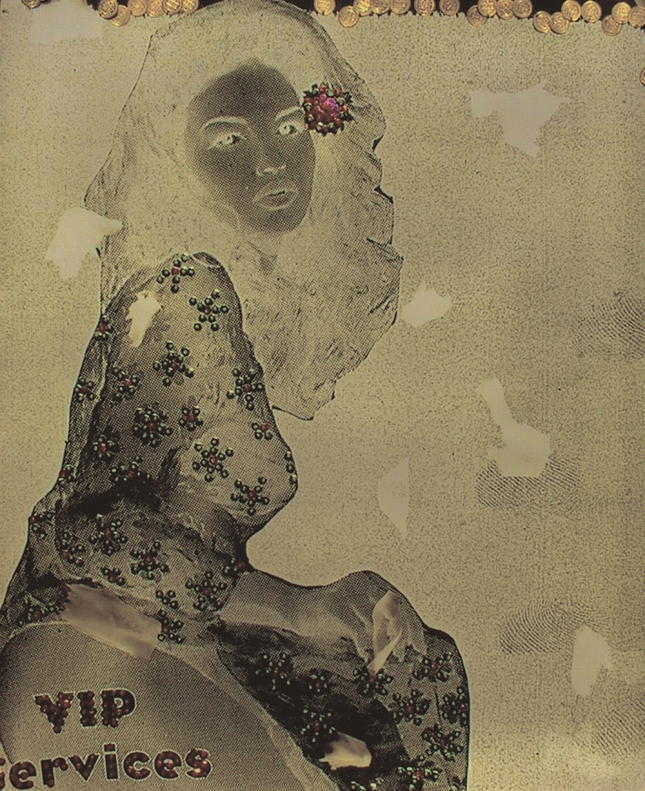

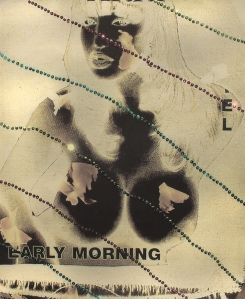

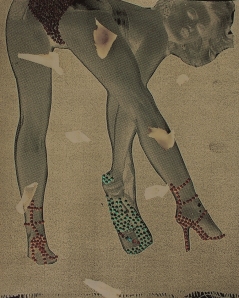

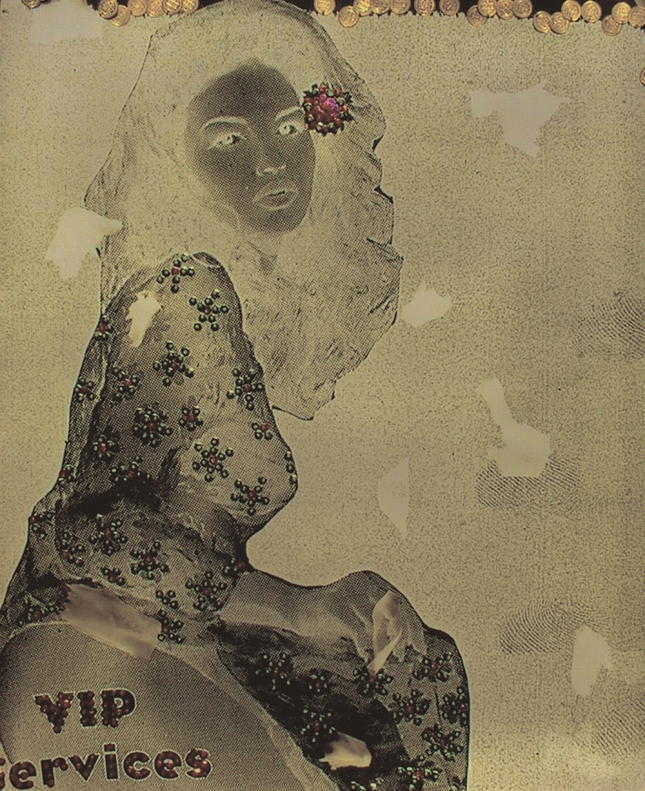

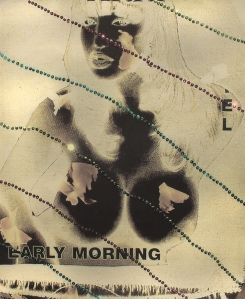

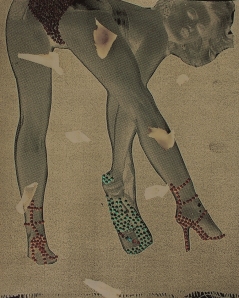

Never the less, as embodying two aspects of femininity, the two series The Black Mother and The Goddess have a point of convergence in that as representations they are halfway between narcissistic self-projection (erotic) and voyeuristic social construction (self-induced trance transmitted to others by look). In the latter series, the sexual visibility of the representations of femininity related both to voyeurism and self-display as they figure in the narratives of culture, is turned against itself in a subversive gesture. The prurient and the surreptitious about them which have been accorded an aesthetic gloss in the fine art traditions in terms of the idealized classic female body, are here laid bare by a kind of vandalisation of the image by erasing its indexicality to become a transformed somatic grotesquerie. The frayed edges, the tattered look of the picture surface, the sequined private parts of the body and the body itself in negative impression, while asserting the aspect of image manipulation as a process in representation, work against any voyeuristic identification with the fetishistic representation of the sexualised female body. The enlarged screen dots on these photocopied images make visible their accessed source and point to the banality of their context of circulation in the scopic regime of mass culture.

GODDESSES / Photography (C) Abul Kalam Azad / Single edition / Sequence on silver bromide prints / 1995

GODDESSES / Photography (C) Abul Kalam Azad / Single edition / Sequence on silver bromide prints / 1995

GODDESSES / Photography (C) Abul Kalam Azad / Single edition / Sequence on silver bromide prints / 1995

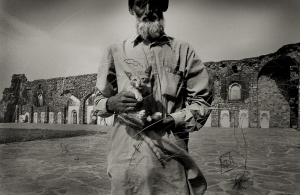

In keeping with his perceptions, Azad historicises the referentiality of the image in a particular way as in the series Man with Tools or the series on animals. Through the staged realism of the anecdotal in the former series he invokes an indirect association of the genre and an allusion to the colonial practice of ethnographic photography. The anecdotal is transformed into a historicized referent signifying the occupation-based social division that had been the ideological base and historical determinant of the caste system and its present day manifestations. And as genre the images seek to thematise the familiar and the socially recognizable in a formally uncoded and under-aestheticised representation of the everyday. All of them are posed photographs of their subjects and the avoidance of anything suggestive of the candid and the spontaneous is a significant deviation from the norm of the genre. This also invests these figures with an assertive self-identity and an awareness on their part of their respective class position, making them rightly the protagonists of historical process. Their look straight out at the camera ready to be photographed make those images more in the manner of posed studio snap shots but used as a visual strategy it establishes the fact of their being a construct. For example, the toddy tapper for whom the ‘tools’ are an identity prop indicating the community he belongs to, for which toddy tapping is the hereditary occupation and hence derives his social context and subject position from the ascriptive caste identity. In a significant twist to the theme, he shows the picture of a young man, apparently a hireling with political connections, happy with himself sitting smugly under the images of his patron saints who are at the same time his tools and for whom he is the tool.

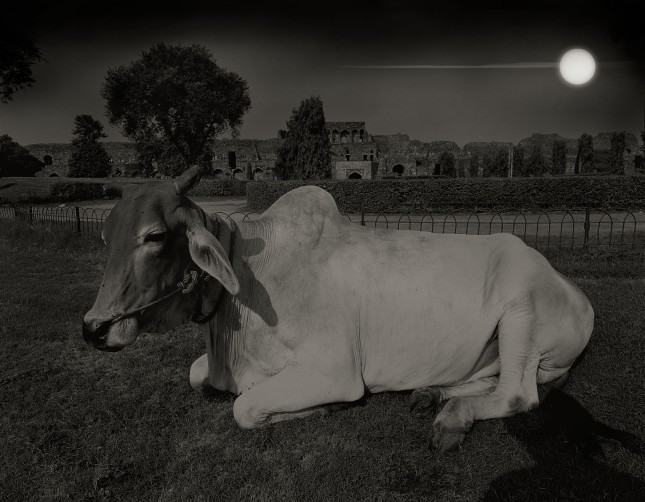

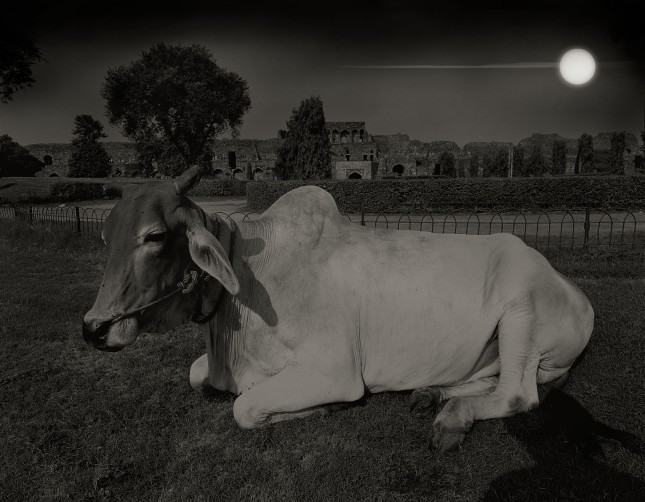

In the latter series, the animals with their ancient totemic associations characteristic of an indigenous tradition and bestowed later with an otherworldly mythical status through appropriation by the dominant religion of the land, have been transmogrified as it were, into an intermediary state between the sacred and profane. As for instance, the image of the prostrating elephant is not that of any elephant; but the partially seen image of the animal is image as metonymy with its mythical associations of the elephant in the Dream of Maya associated with the birth of the Buddha which has many sculptural representations in ancient Indian art. If the use of metonymy here is expressive of a kind of perspectival ambivalence between representation and indexicality, sign as metonymy inflects meaning from the referential of the represented image, in this case, through intertextuality.

Digital Moon / Photograph (C) Abul Kalam Azad / Archival pigment prints / 2006

Digital Moon / Photograph (C) Abul Kalam Azad / Archival pigment prints / 2006

Digital Moon / Photograph (C) Abul Kalam Azad / Archival pigment prints / 2006

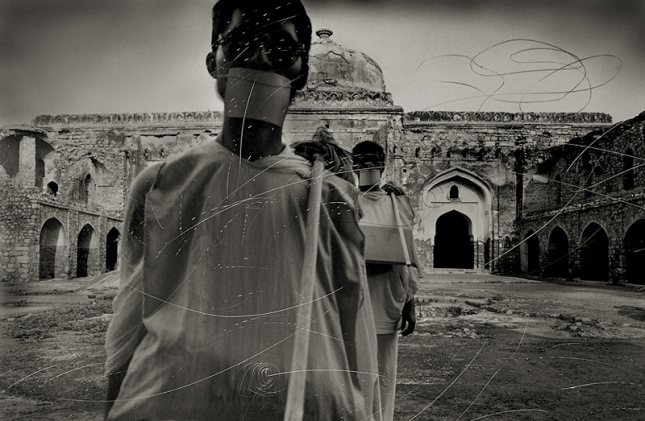

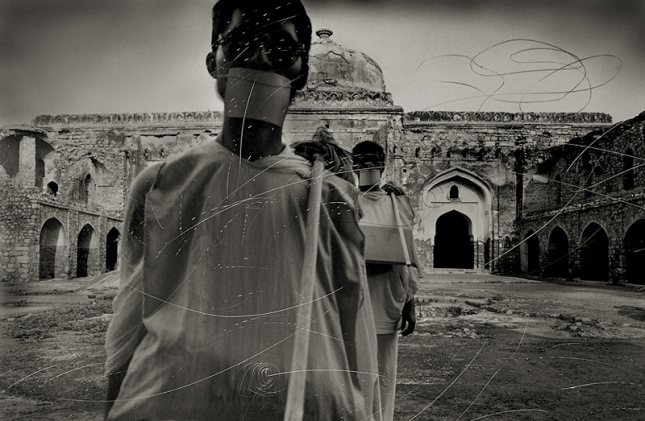

His concerns both photographically and ideologically come to a point of convergence in the series the Divine Façades. Here also the human figures are self-consciously posed but are foregrounded in the frame and take their place in front of historical monuments. The dominant spatial relations as articulated in the various interpersonal modalities of behavioural spaces in a society gain a particular cultural visibility as embodying the institutionalised patterns of inter-subjectivity. In this series of photographs Azad uses photography as a means of engaging these dominant spatial relations and of re-spatialising the human figure in its relation of an anonymous presence to the public sphere. By subverting the normative human module of classical proportions Azad creates an unobtrusive spatial disjunction between the figure and the ground that throws the scale relations into disarray which is made the more so by the discreet use of differential focus between the frontal figure and the ground. The result is that the use of foreground details that are at times conspicuously truncated by the frame evoking a metonymic referentiality in relation to the human figure which itself is less in focus than the background including the historical motifs, allows the space of human presence to be inscribed with a certain transitoriness of temporality that moves it out of the theme of history. The stillness of archaeological distance of the background comes into interaction with the live human presence which at the same time activates a spatial and temporal immanence of which the historical motifs are themselves a part, for it to engage with. In fact, in a work that is singularly distinguished in the whole series – the photograph with an outstretched hand almost covering the lens – Azad asserts that he has still resort to the pictorial and graphic means of visual resources to make a point photographically. The outstretched hand in a gesture of covering the lens and by extension, of blotting out the image, is a connotative manipulation of the part object (the hand) to signify the powers at work to suppress and to gag freedom of expression. The choice of a slightly low angle accentuates the directional opposition between the two axes of the hand and of the monument, to pull apart violently, thus dramatising the spatial articulation.

Divine Facade / Photograph (C) Abul Kalam Azad / Single edition / Doodles on silver bromide prints / 1995

Divine Facade / Photograph (C) Abul Kalam Azad / Single edition / Doodles on silver bromide prints / 1995

Divine Facade / Photograph (C) Abul Kalam Azad / Single edition / Doodles on silver bromide prints / 1995

Azad’s method of working in a sense seeks to be aligned as much with the tradition of the artist’s print as with photography itself as is borne out by his painstaking use of layering and superimposition in the large digital prints on canvas, his use of bromoil to achieve a jaded, archival quality in his monochrome chemical prints and his manner of scratching the negative to debunk the aura of the unique, all in a gesture of resistance to the slick and glossy finish of commercial photography. Where he resorts to the digitally reprographic resources of image production, as he does of late, it is because it offers the image to be “reproduced” as image-units that can be worked over and deployed as it were, in multiples and serials in various compositional schema. These images as recurring motifs in their connotative function are like morphed mutants, so to say, that keep reappearing in different configurations with minimally variable attributes and go to make an intertextuality at the level of discursive meaning representation.

Prof. R. Nandakumar

Thiruvananthapuram,

November 2007

*John Roberts, The Art of Interruption: Realism, photography and the everyday, (Manchester University Press 1998), p. 148

(C) All rights reserved. All the images published in this blog is copyrighted property of contemporary Indian photographer Abul Kalam Azad. Text (C) Prof. R. Nandakumar. Reprinting / publishing rights reserved by the author and prior permission is required for reproduction / re-publishing, For more information call {0}4175 237405 / {0}94879 56405 or mail to ekalokam@gmail.com / FACEBOOK – Abul Kalam Azad